Materiality

With digital tools as a standard for creating images, it might be tempting to see the objects as a pure visual shape, be it physical items or digital models. Nevertheless, that is not how we perceive objects—to understand them better, we need cues about how heavy they are, what the surface feels like, and so on.

Tactility is understood through materials, and in this research, we are going to look at how artists and designers examine materials and our relationships with them.

Materials as seen by artists

The separation of art and depiction of scenes from real life in the 20th century led to a number of art movements that were interested in working with raw materials. As some artists arranged their abstract sculptures in a certain way, others gave only basic instructions and organized material so that there was some extent of randomness in how the installation was constructed.

The method of letting the material behave somewhat freely was used by Robert Morris, an American abstract sculptor who started exploring the possibilities of different materials in the 1960s. One of the series that embodies the principle is The Felt Works, for which Morris created sculptures made of thick felt, which were hung on a wall.

The focus of the artist was on the material itself and its interaction with gravity and its environment.

The series included several ‘tangled’ pieces, in which this principle is especially evident—they were inspired by the work of Jackson Pollock and, according to Morris himself, were an embodiment of entropy and showed the process of creating an artwork.

A contemporary of Robert Morris, Richard Serra is another artist from the US who was moved by Pollock’s techniques. He intended to explore how the material changes the way a viewer behaves and moves, to widen up the space of artwork, and to include the visitors of an exhibition inside of it.

In the 1960s, Serra created installations that reminded felt pieces by Morris—called scatter pieces they consisted of ribbons made of rubber and latex, diffused on the floor.

His method during this period relied on the list of 54 verbs, which described the way the artist could treat the material, i.e. to bend, to wrap, to stretch, and so on.

To scatter was one of them, and the goal of the whole approach was to figure out the logic and the behavior of materials.

Another artist who let the materials lead her practice was German-American Eva Hesse. Working with latex, fabrics, and ropes, also in the 1960s, she was treating her artworks as a space for experiments.

While Hesse draw sketches for her installations, these images captured the general mood and the final shape of a piece was defined in the process.

Using this method, the artist created works that looked organic and reminded of human bodies, standing out from the legacy of other abstract sculptors.

In Japan, the Mono-ha movement had a similar interest in materials as their counterparts in the US but a different approach. For the Mono-ha artists—Nobuo Sekine, Lee Ufan, Kishio Suga and others—their work was an attempt to reduce objects to their primary form and to study materials as self-sufficient and significant.

When an artist put the material in a certain space, they created a non-hierarchical structure, including the object, space, the artist, the viewer and even shadows, in which every part was equal. The focus was not on the piece but rather on the net of connections that it created around itself.

Material awareness in design

Materials drew designers’ attention with the rise of functionalism, a movement that proclaimed that the function of an object should define the way it looks.

Exposing underlying structures and using materials without decoration, proponents of the approach endorsed not only a new ‘clean’ aesthetic but also rational use of materials, caused by a caring attitude towards them.

This idea of material awareness is more relevant now, amidst the global climate emergency. There are several techniques for bringing this vision to life, one of them being the reuse of materials.

More and more designers across the world accept this method, for instance, using food waste to create alternatives for leather or building furniture out of ceramic waste or marble offcuts.

These objects are not mass-produced and, therefore, available to a limited number of customers, but they show another way of production, focused on obtaining materials locally and using innovative methods to produce new items out of old ones.

The biodegradability of materials is another important property that gets the attention of the design industry.

A relatively new field of research, the production of biodegradable materials sometimes leads to controversial results—some ‘compostable’ plastics decompose only in special equipment, yet people might throw these materials away with other organic waste.

Still, the search for more environment-friendly substances has massive potential to bring about new kinds of materials. One of the recently discovered types is based on fungi.

Plant-based waste, such as straw or sawdust, is put into a form and filled with spores. As a mycelium grows, it connects the substance into a solid ‘brick’. This material is already used in packaging and furniture and might probably be used in larger objects and even buildings.

Not only the ecological impact of materials matters in design but also their sensory and emotional characteristics.

There are efforts to create tools and techniques for industrial designers, through which they could explore materials through their senses and direct interaction.

Such tools include samples that can be used during the design process, databases with examples of products made of the particular material, and guidelines including technical properties alongside impression and usability.

Our research

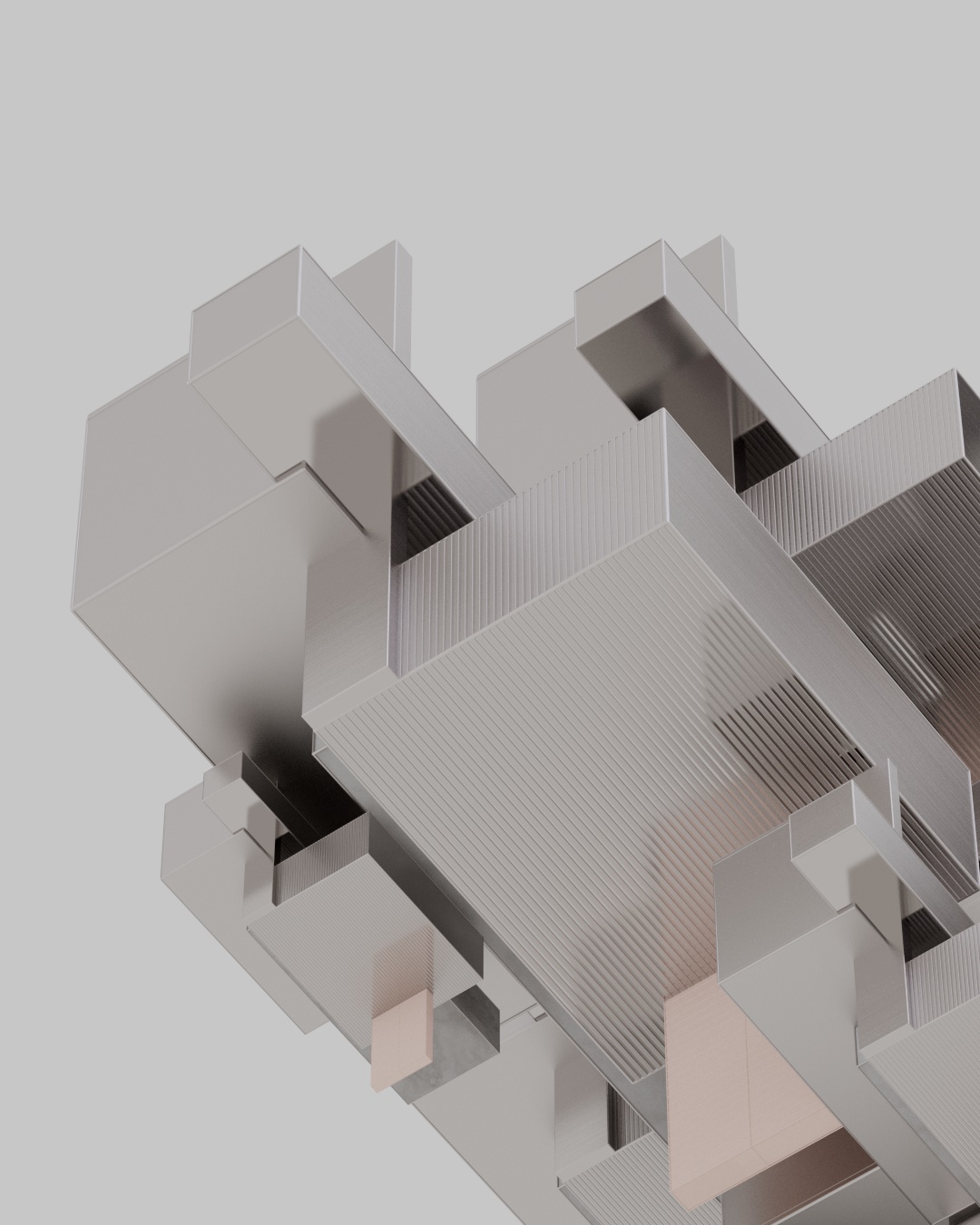

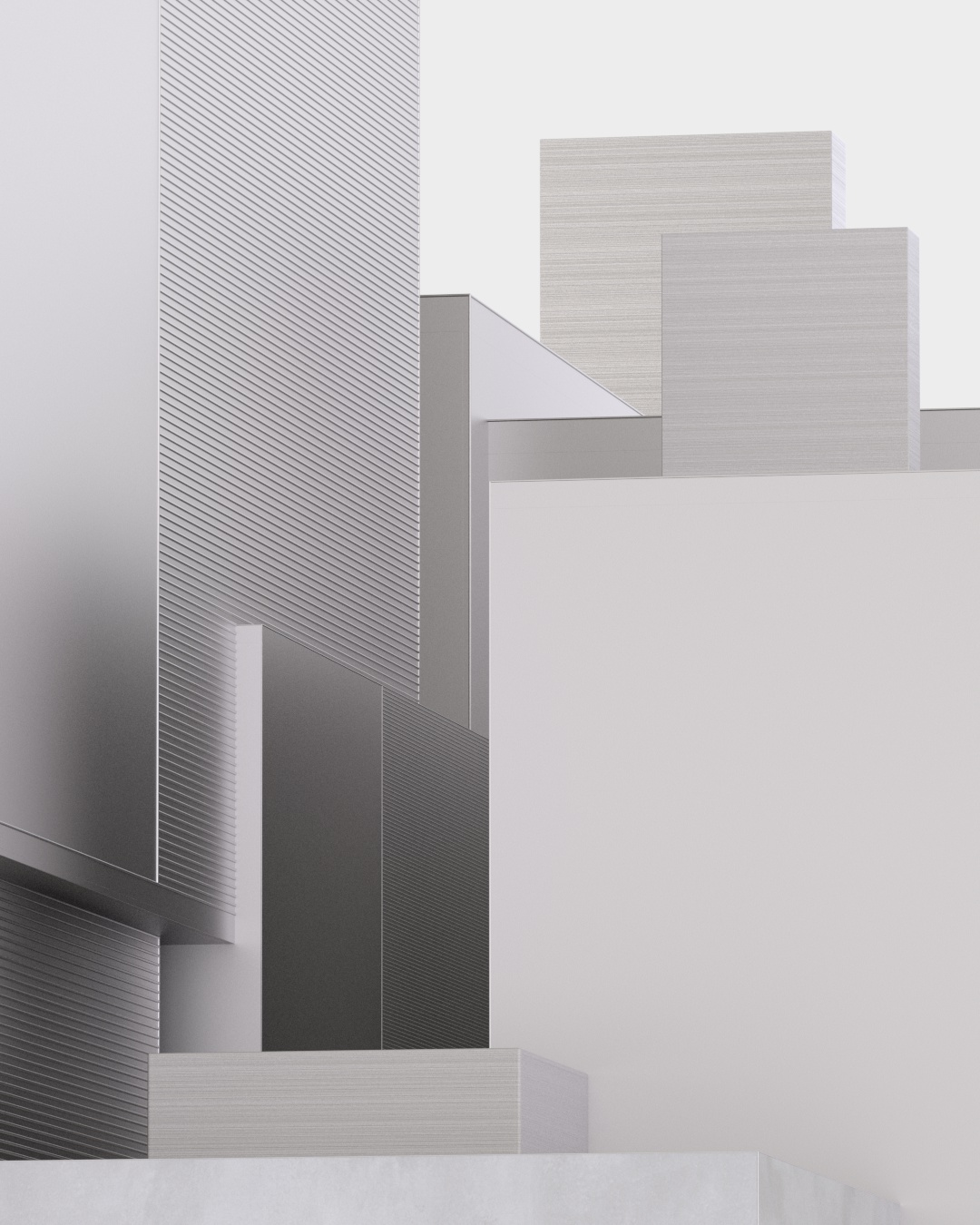

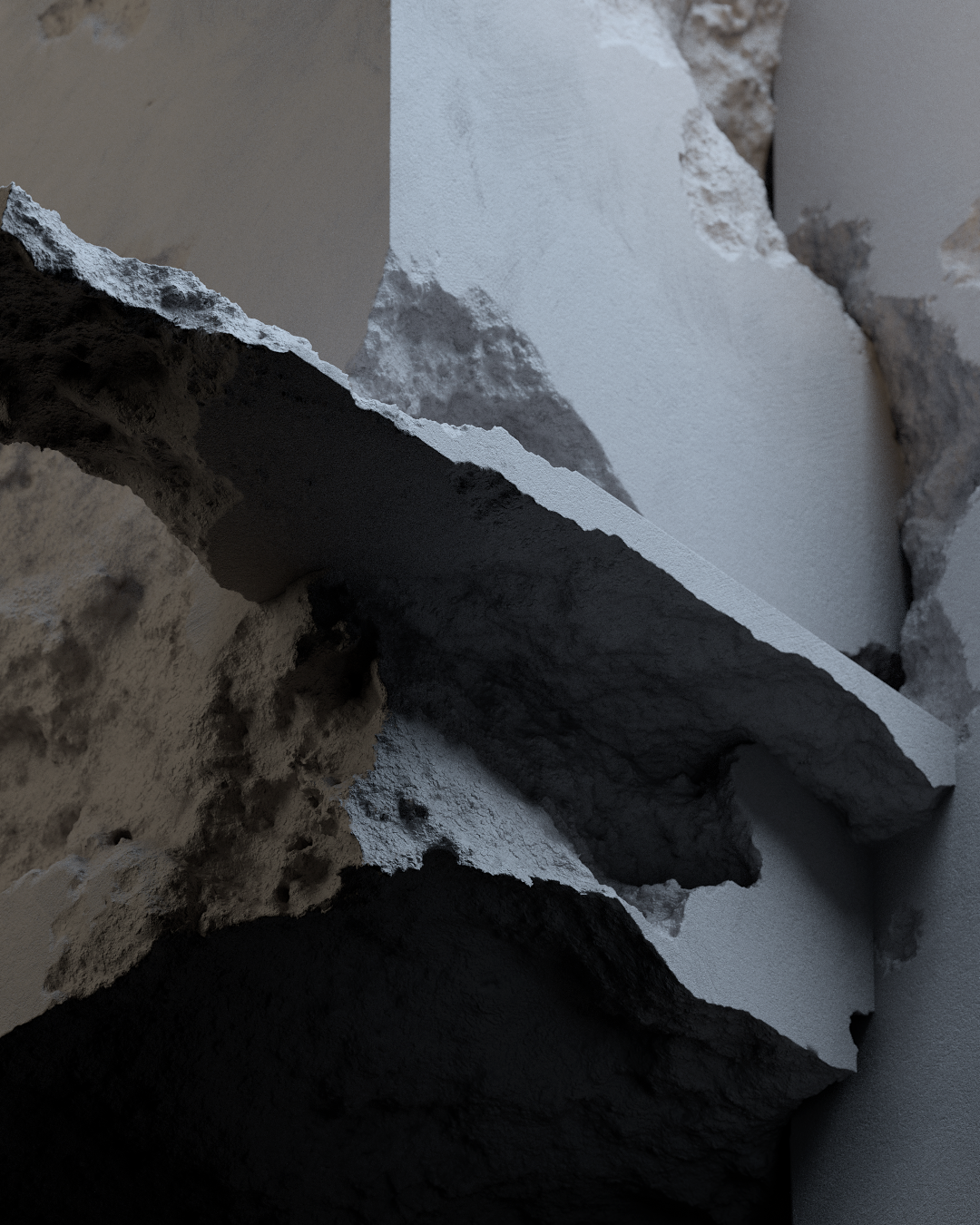

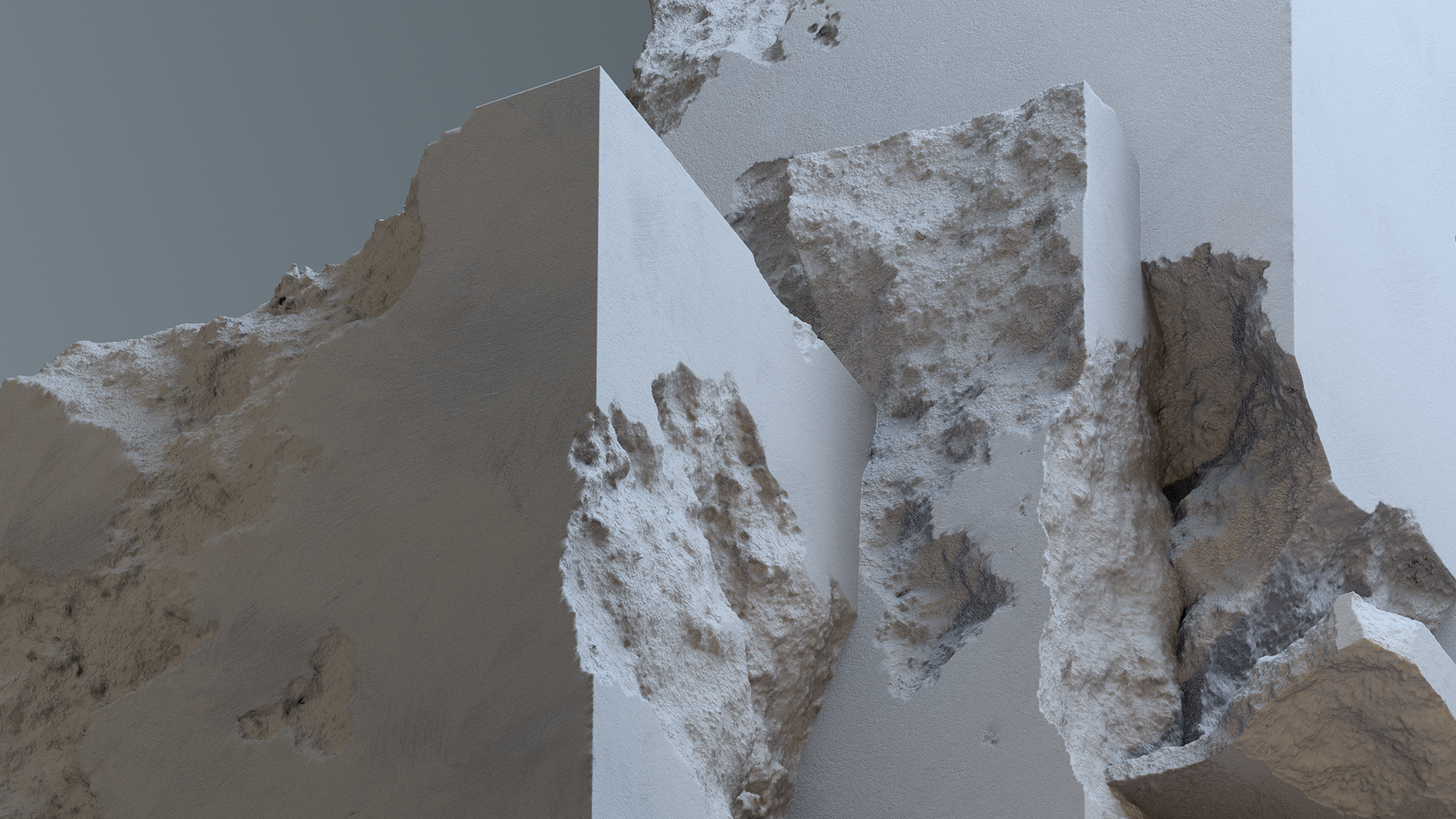

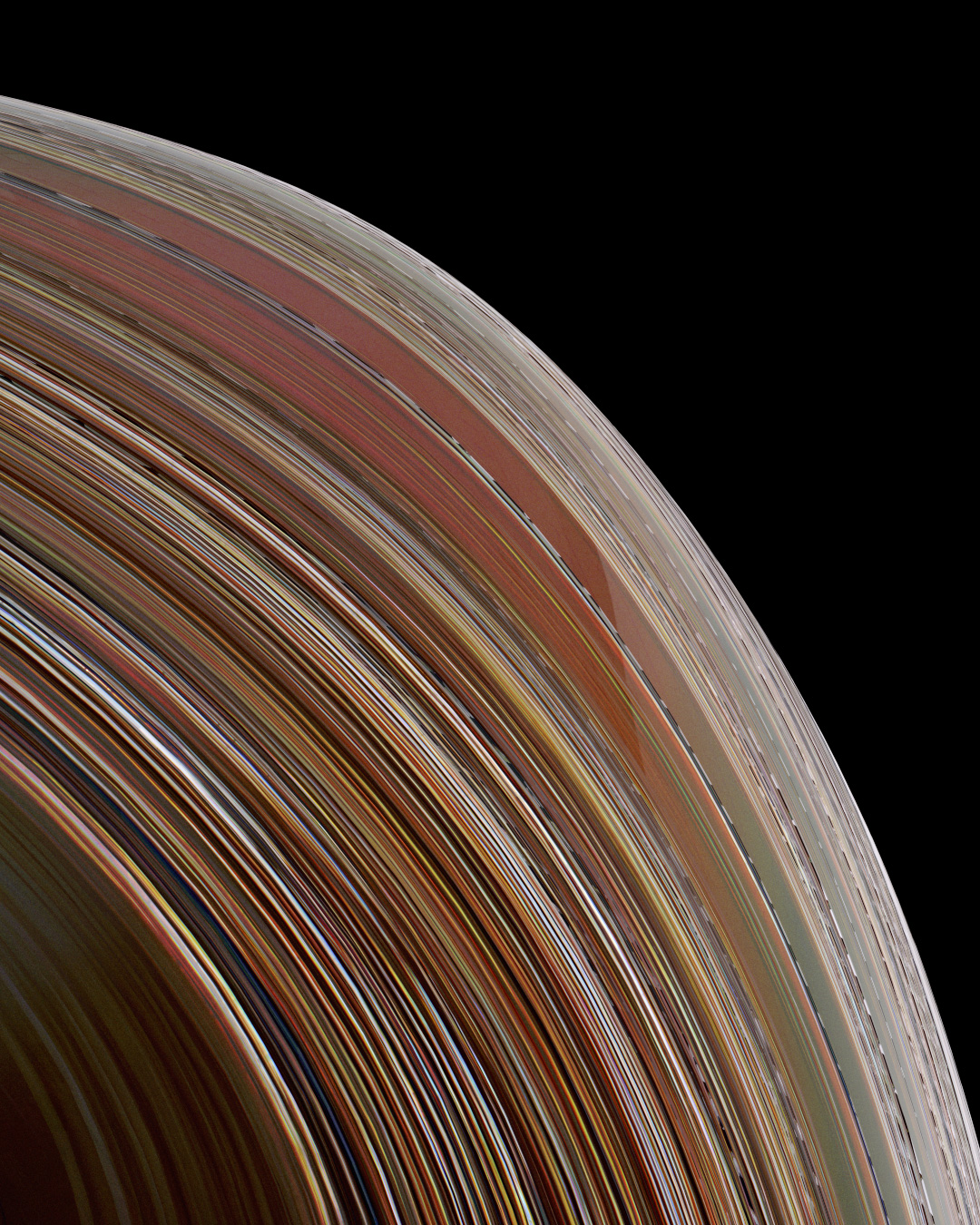

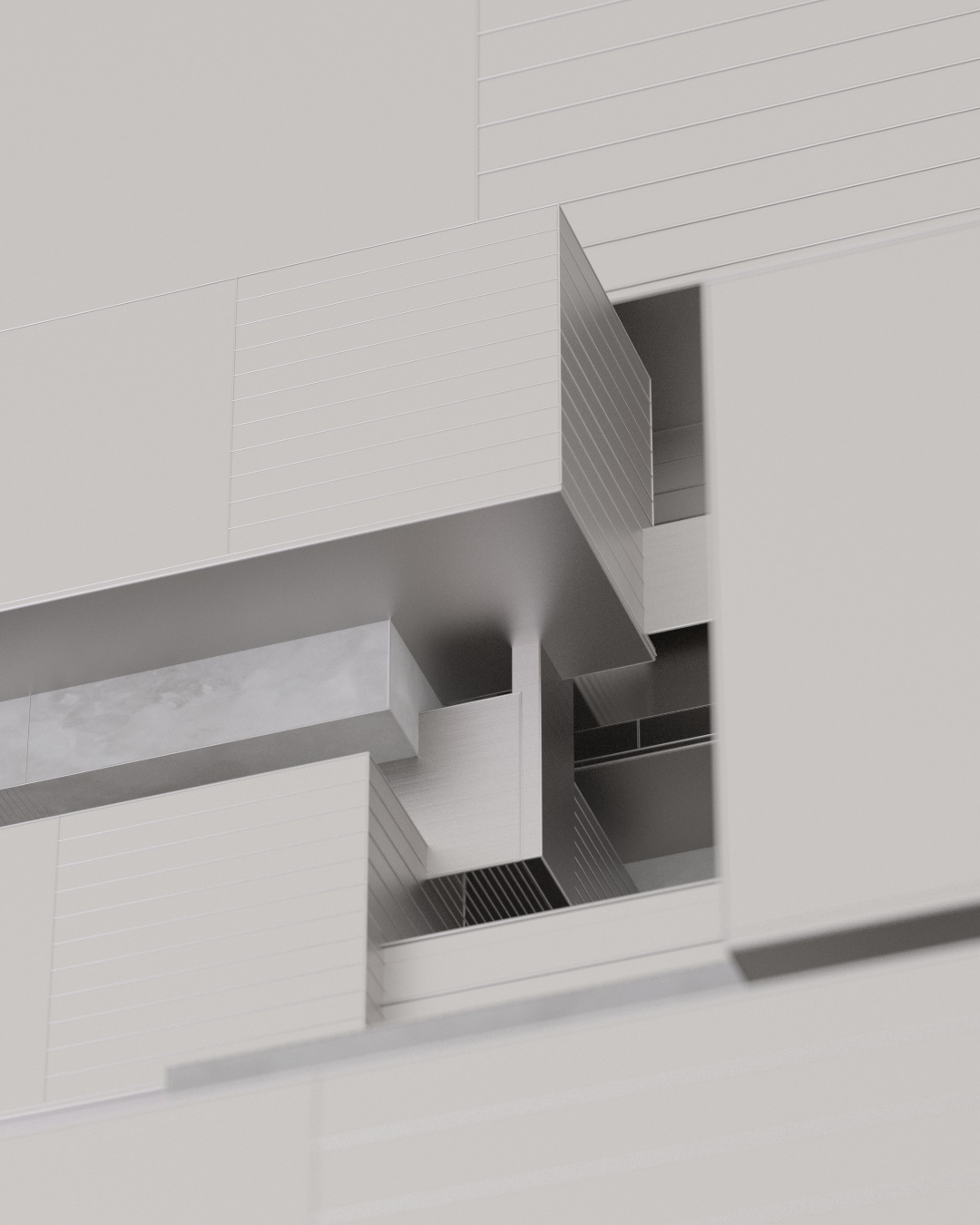

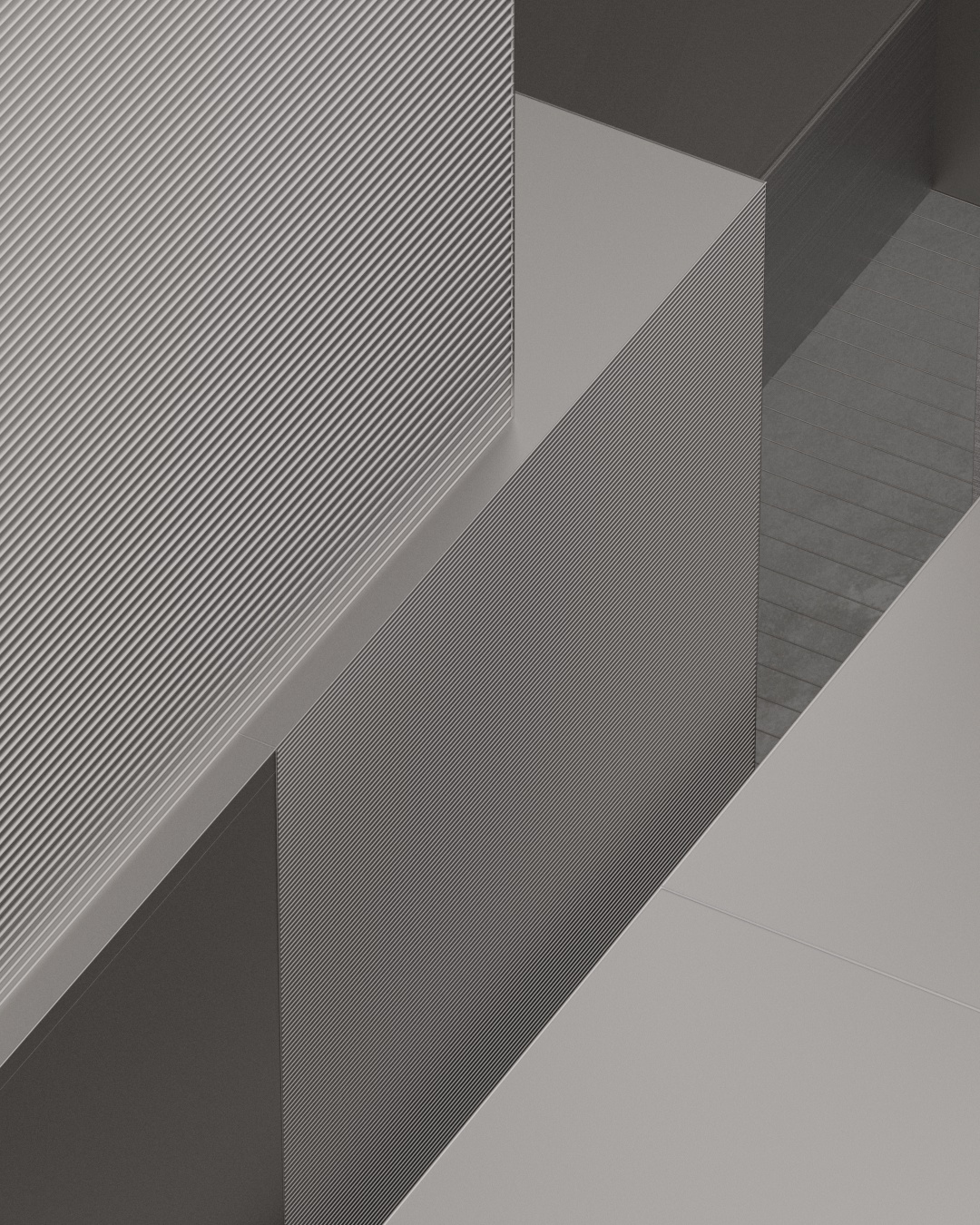

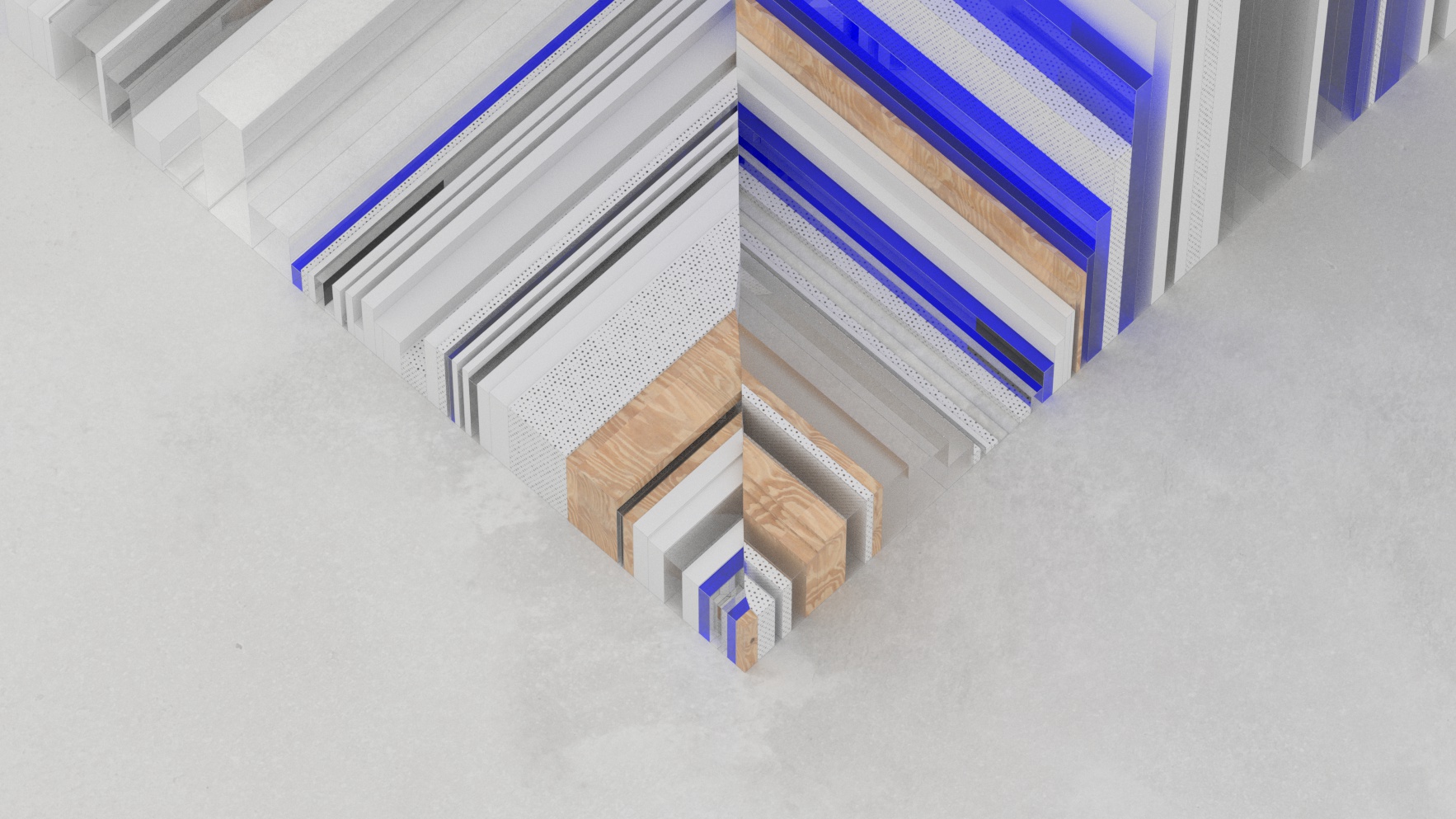

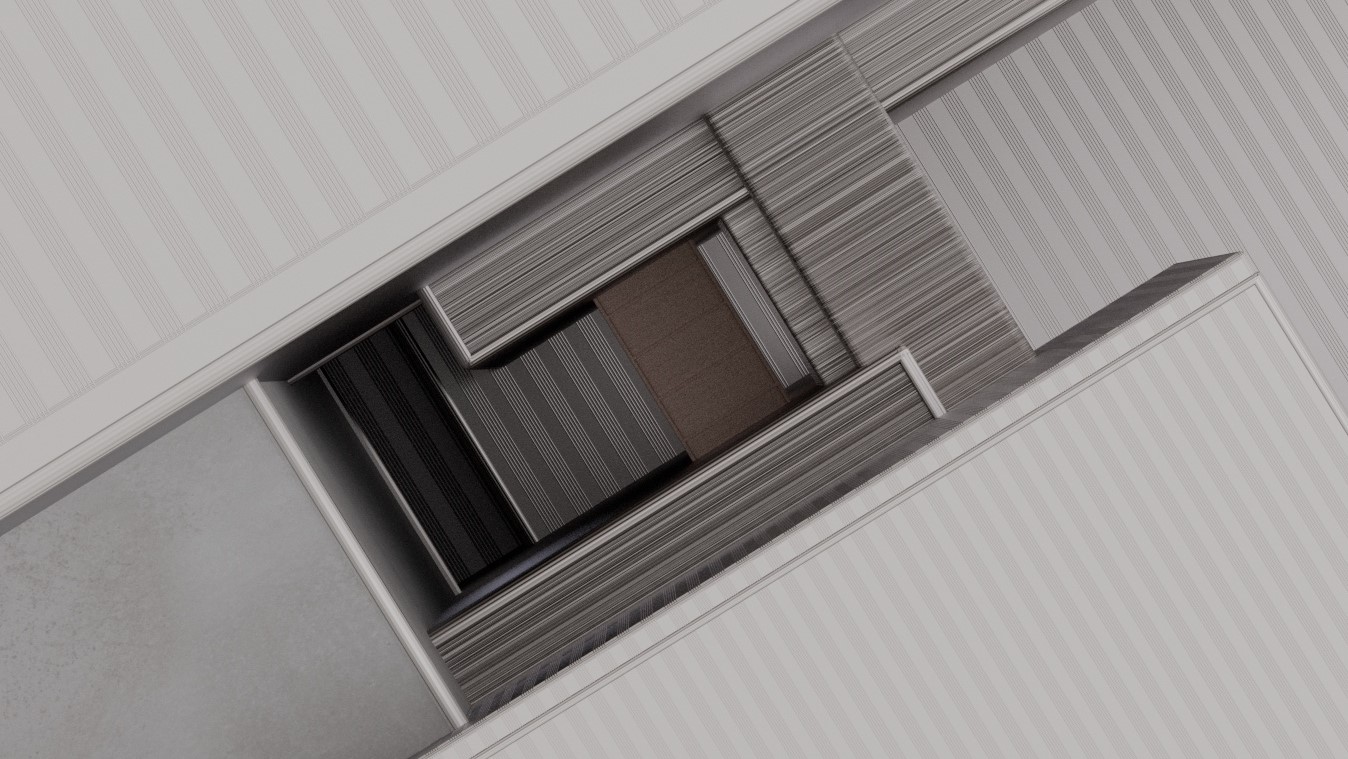

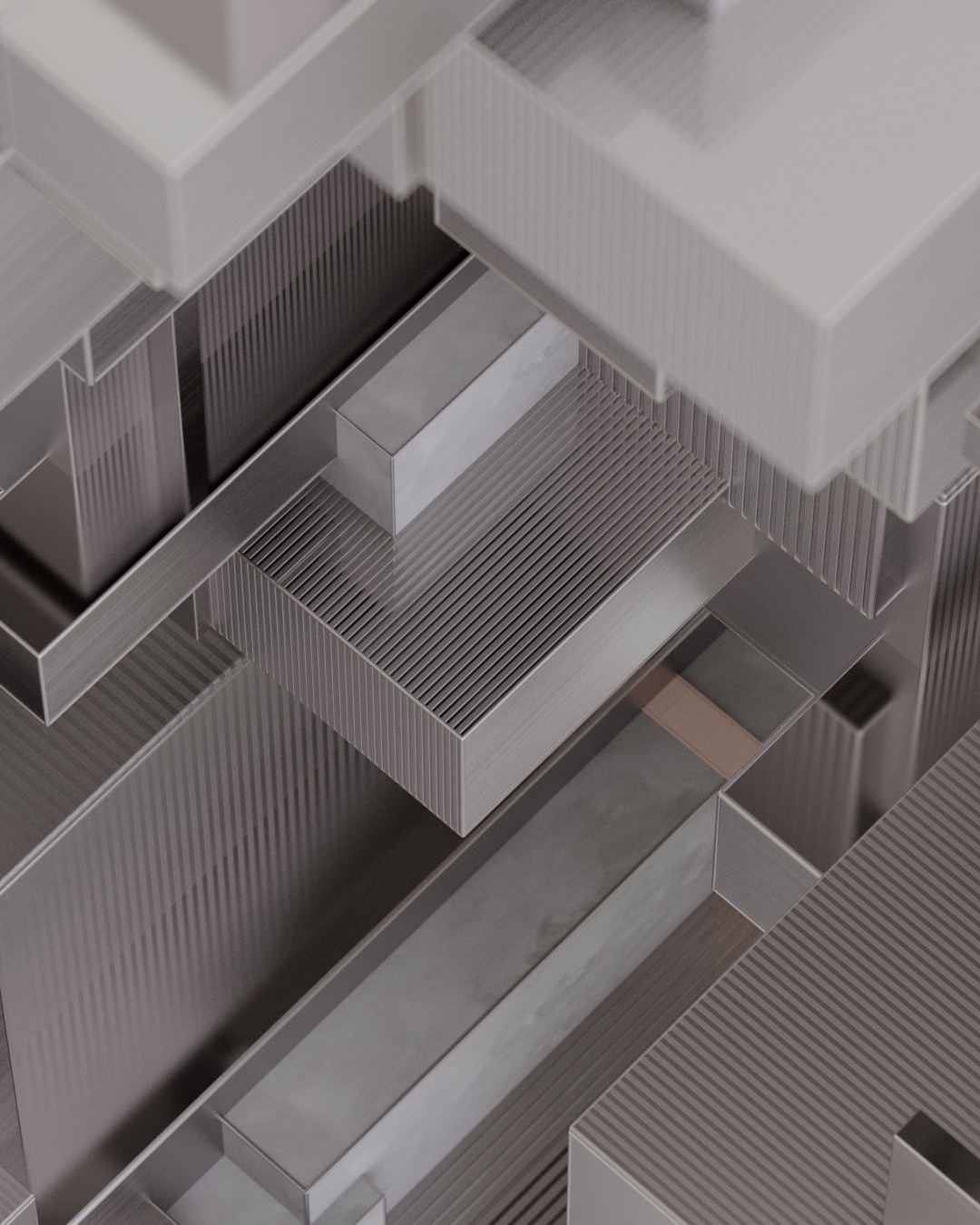

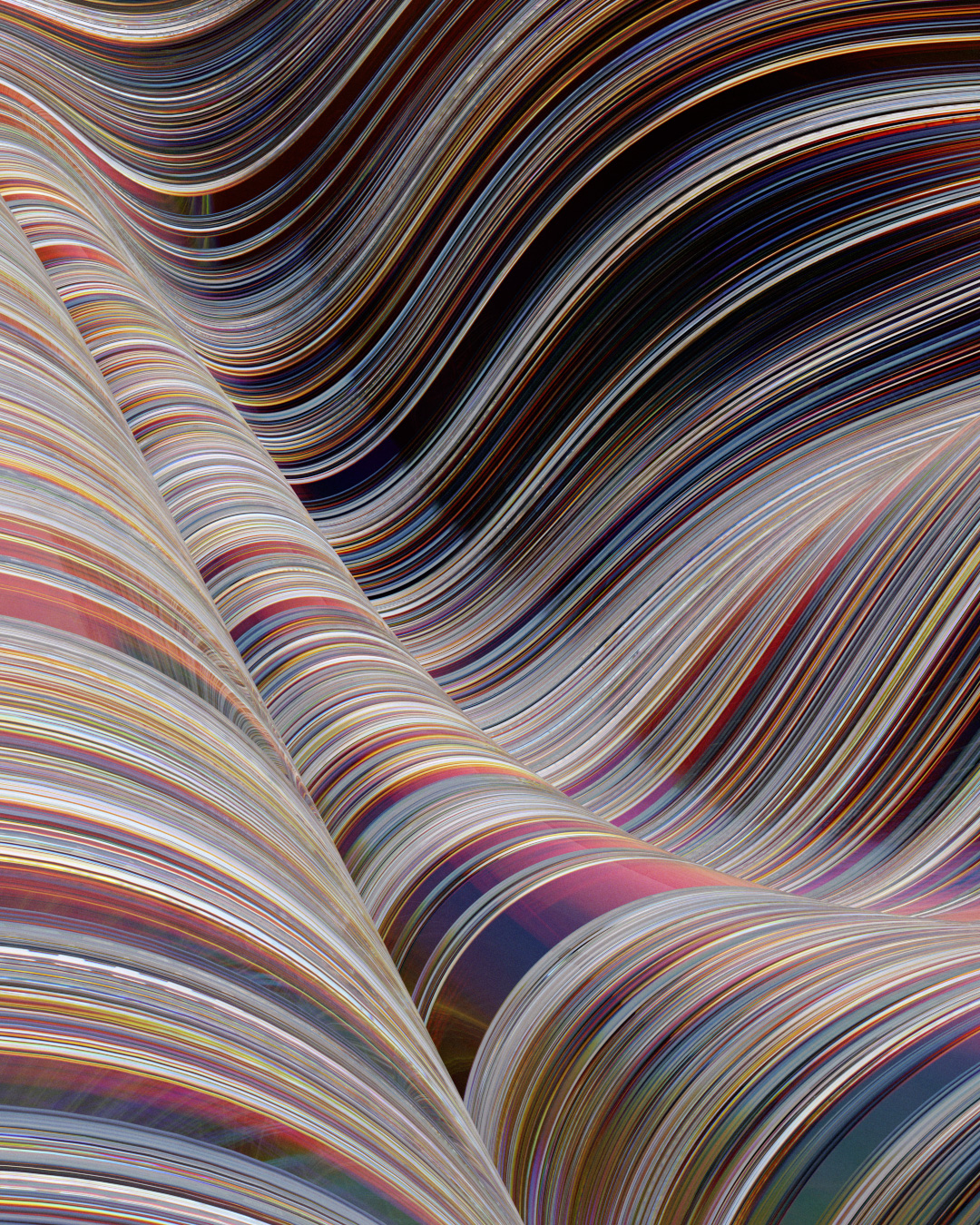

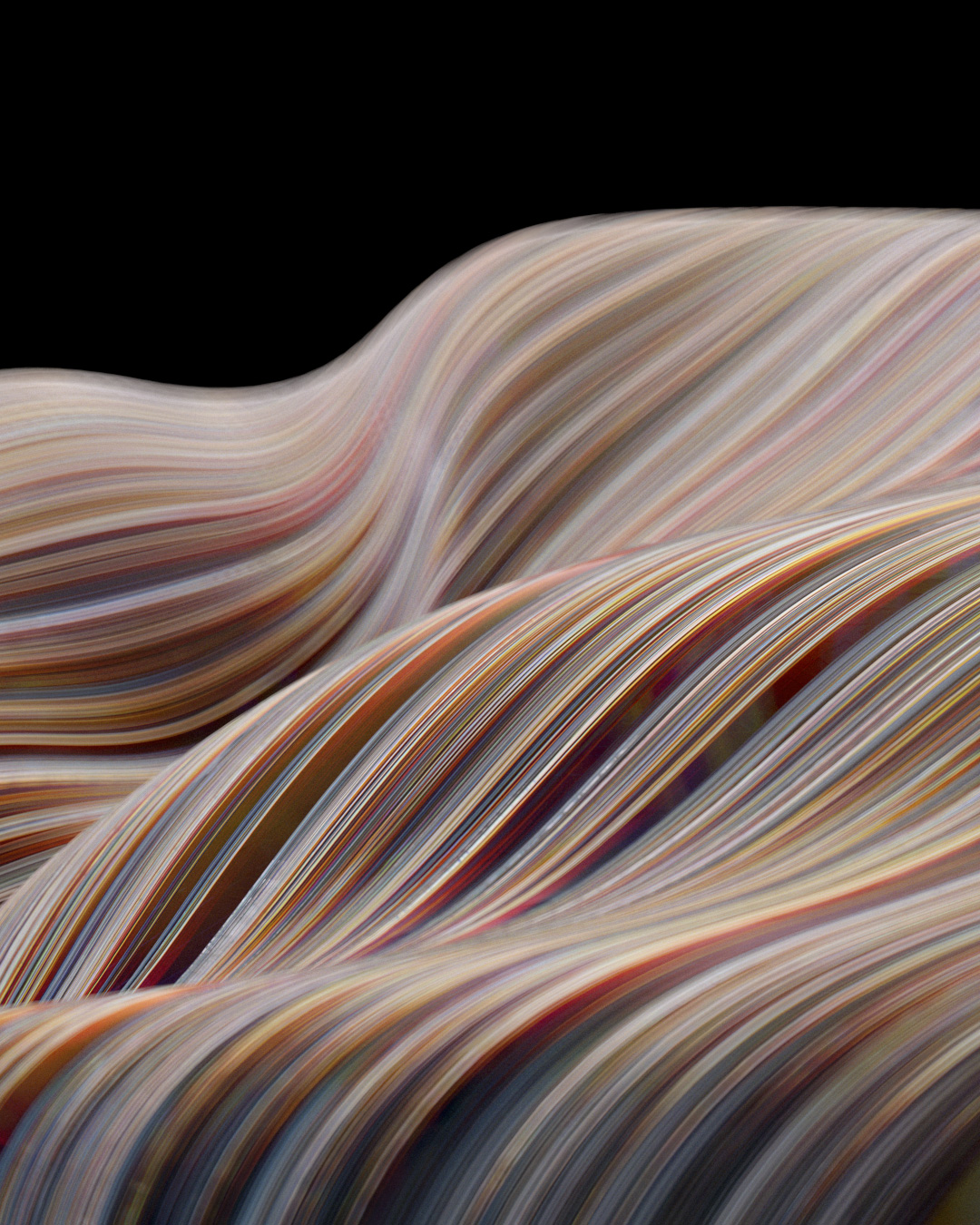

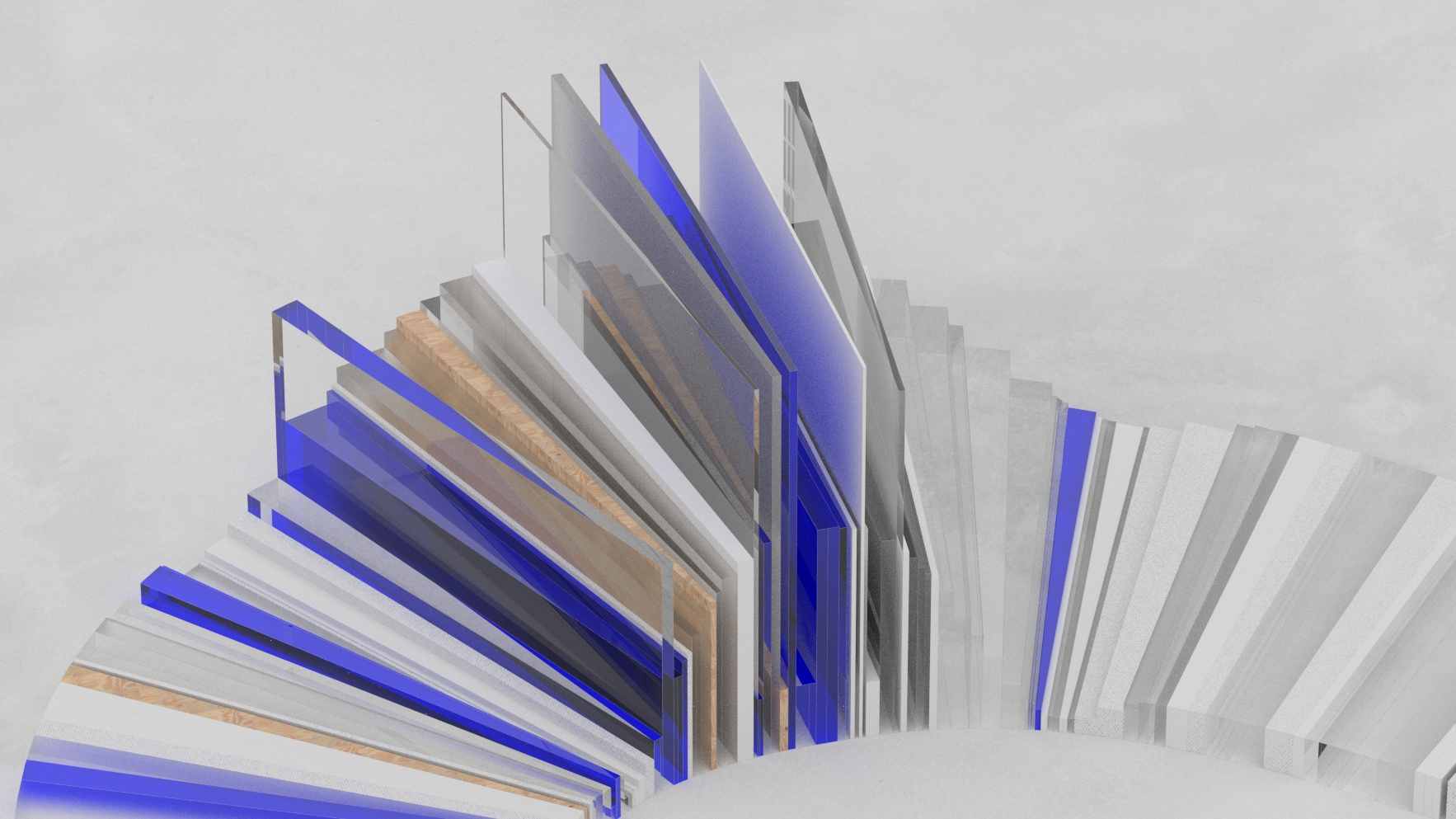

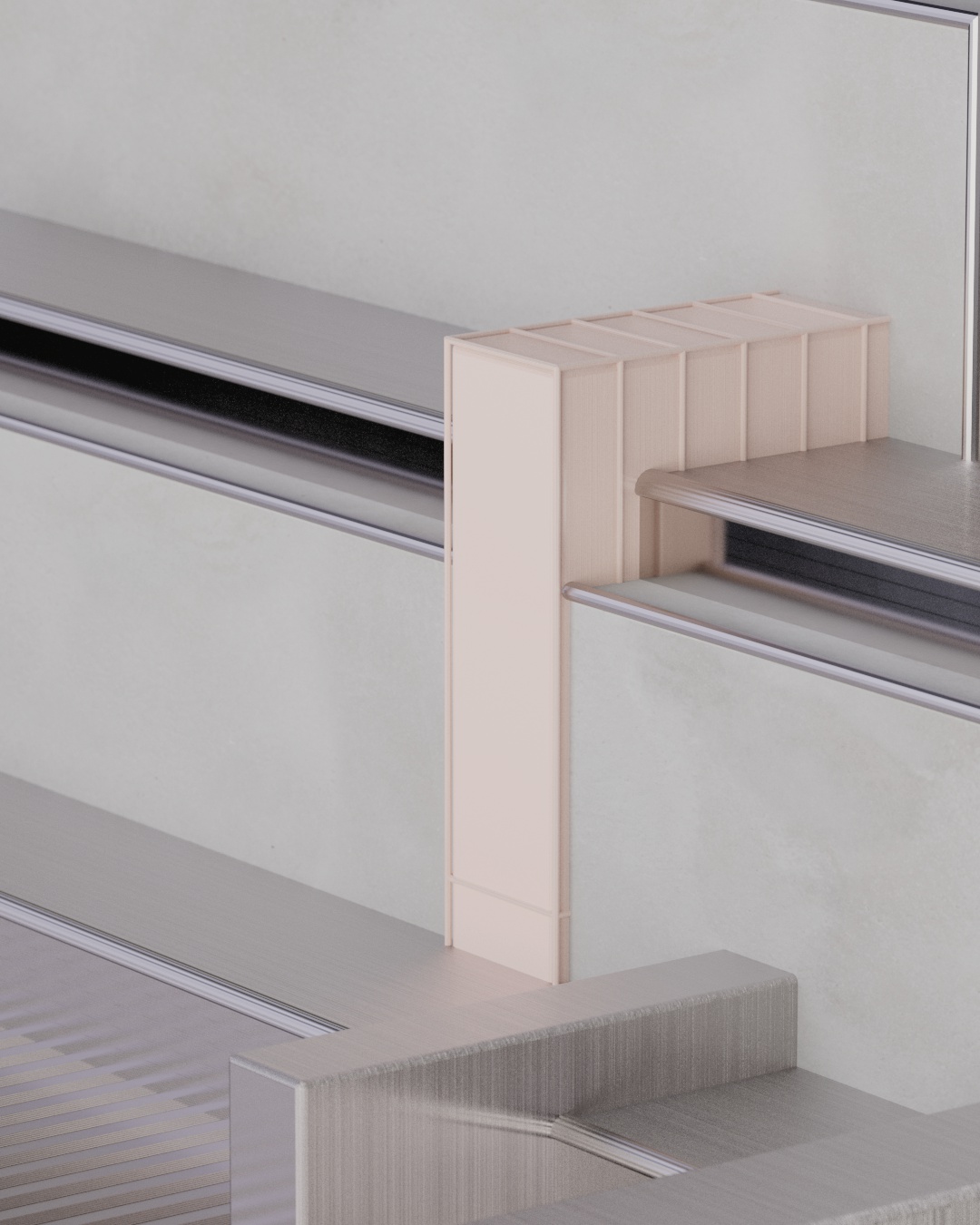

Our works included in this research, are focused on the representation of materials in digital environments. Examining light, textures and interrelations of objects, we worked with perception and tactility of images and created abstract images, imbued with possible associations.

While some of the tests turned out to be minimalistic and dedicated to studying only color and texture, some resulted in imaginary objects and tiny worlds, giving us ground for further explorations.

Credits

Creative Direction:

Maxim Zhestkov, Igor Sordokhonov

Design, Art Direction, Animation:

Sergey Shurupov, Oleg Zvyagintsev, Dmitriy Ponomarev, Denis Semenov, Artur Gadzhiev, Artur Zhamaletdinov

Writing:

Anna Gulyaeva

Year:

2020

Contact us >

work@media.work

Follow us >

Instagram

LinkedIn

Spotify

Media.Work > USA

453 S Spring Street

Ste 400 PMB 102, 90013

Los Angeles

Media.Work > UK

71-75 Shelton Street

WC2H 9JQ

London

Media.Work © 2024