Designing the Future

Celebrating the revolutionary power of design, we drew our attention to speculative design and experimented with concepts of devices. See what we created and read our short research about design fiction and its place in our world.

More often than not German school Bauhaus is considered to be a starting point of modern design. One of the principles of Bauhaus was that the objects created in the school‘s workshops were intended for mass production. With the ongoing industrialization led by Great Britain, Germany, and the USA, this approach spread across the world, resulting in the increasing interest to design, especially industrial.

As industrial design deals not only with pure aesthetics but also with the relationships between the object and its environment and, more importantly, between the object and a human. Because of this thoughtfulness, we are surrounded by products that are constructed with regard to our habits, behavior and other peculiarities.

Most apparent this method is in the modernist design, especially in ‘organic’ designs for furniture and household items made by two famous designer families—Aalto and Eames. Their approach was to create products comprehensible by everybody and to make good design available for the masses. That could not be achieved without the ease of production.

While it is quite easy to construct furniture that will be understood, new devices or vehicles may be too bizarre for a customer who encounters the technology for the first time. To deal with this confusion, legendary industrial designer Raymond Loewy suggested the principle ‘MAYA’ — More advanced. Yet acceptable.

This means that every new product should remind of something already existing. For instance, when startups define their product as ‘Uber for X’, they use exactly this method.

The reverse side of the MAYA approach is that sometimes brands tend to release new products that do not significantly differ from older models.

This tendency can be critiqued for the artificial magnification of production and consumption, controversial during the ecological crisis. Creating the products only for the sake of saturating the market with something new diminishes the subversive potential of design to the mere function of serving the manufacturing.

Seeking the alternative, designers turn to work on concepts that are not supposed to be mass-produced and sometimes can’t be produced at all. This activity is called design fiction, or speculative design, and its goal is to tackle large societal problems, to create new possible futures, and to do that without thinking about the current limitations of technology and science.

Proponents of the approach, Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, who wrote a book on speculative design, suggest a classification of futures, which includes three options: possible, plausible, and probable options, the latter one being the most realistic.

Speculative design mostly deals with preferable futures that lie at the intersection of plausible and probable—not exactly sci-fi scenarios but something less common in modern design.

The purview of design fiction is wide enough to include projects with different extents of probability. Some of them might be quite possible to create in the real world, like ‘Microbial Home’ created by Philips Design.

This concept describes a home that operates like an enclosed ecosystem, where the waste can be converted into methane and used to power the house. Some ideas are way more unconventional—a company called Planetary Resources planned to mine asteroids passing the Earth and even was backed by investors.

It is also worth noting that this approach is not purely optimistic and promising. Another definition of speculative design is that it deals with future problems instead of current ones. In this sense, the famous series ‘Black Mirror’ is also considered to be close to design fiction, as it tells about the potential amplification of our current tendencies in technological development.

Our research

For one of our weekly explorations, we divided into three teams, each received the task to create a prototype of a physical object. It did not necessarily have to be in the realm of speculative design, yet some of the created items deal with experimental technologies not seen in mass-produced products.

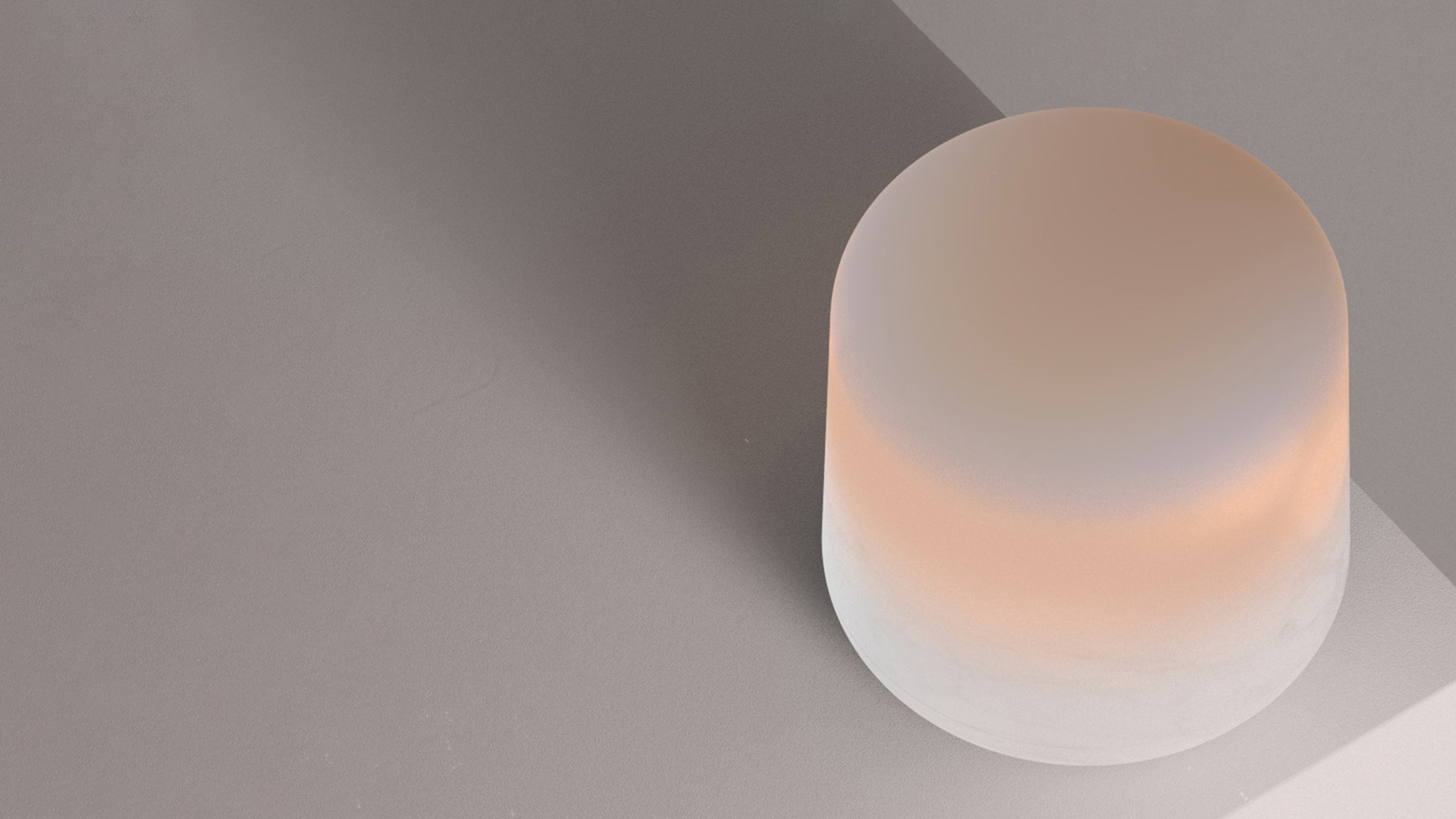

The first object has the potential of being mass-produced—it is a lamp, in which light passes through layers of colorful materials that can be easily switched to anything else.

This is an item which is supposed to be customized and which can change the mood in the interior completely by simply changing the ‘lampshade’—it can create shaped shadows with texts or images and mix different textures, being a playground for its user.

The second item that was born in our ‘lab’ is an air purifier and a flower pot at the same time. It creates perfect conditions for a plant that grows inside of it, in a glass shell, and uses this plant to clean the air.

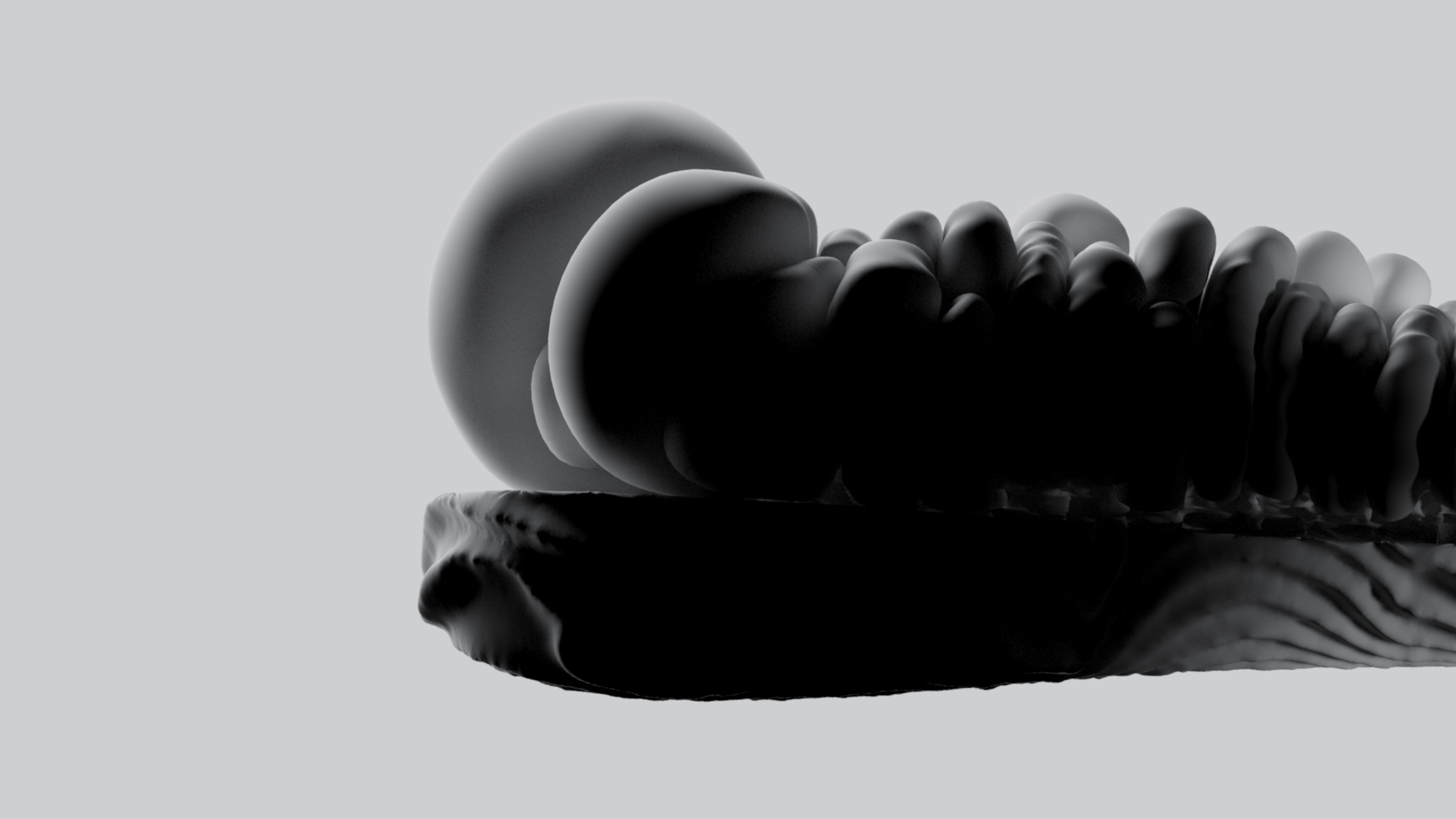

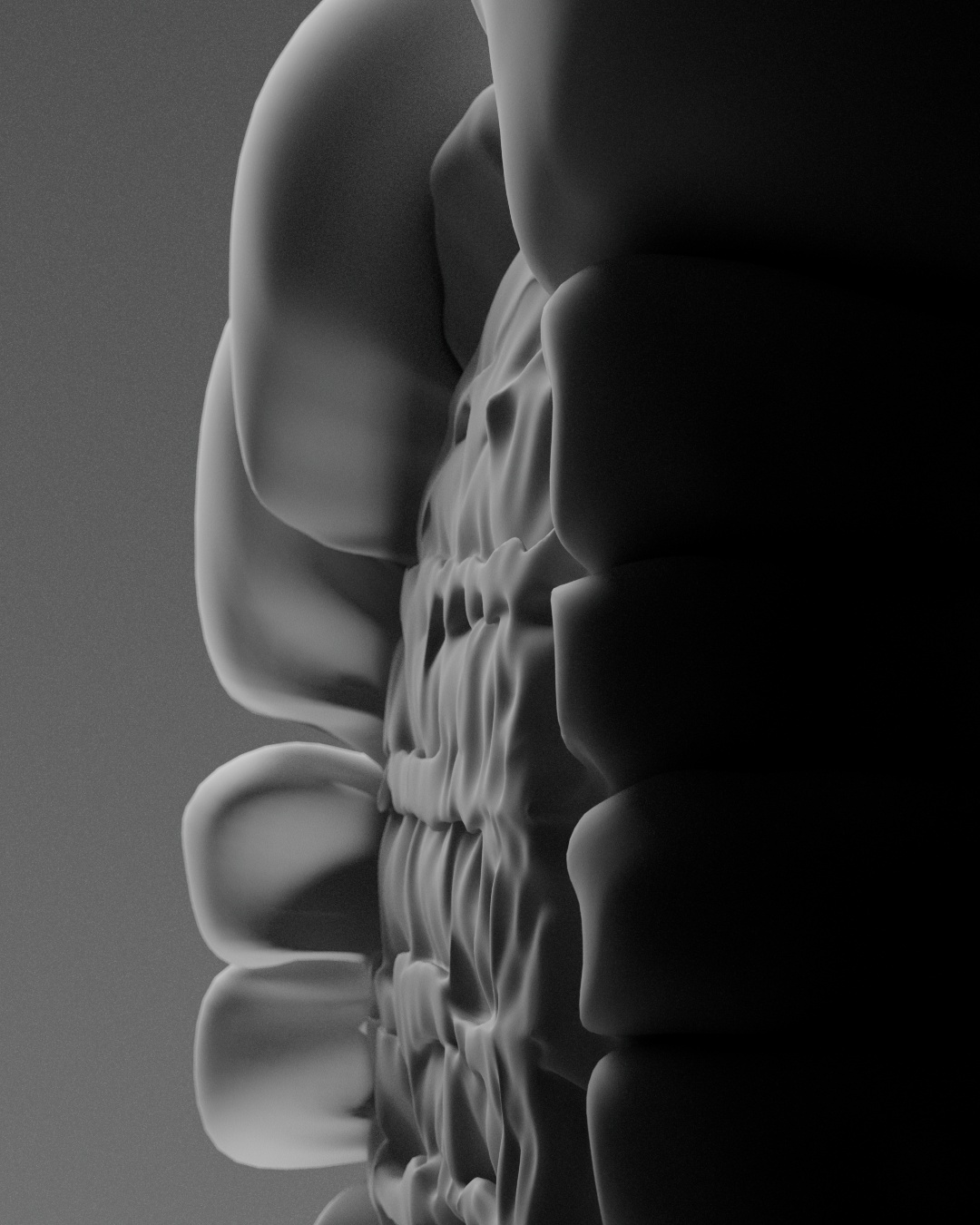

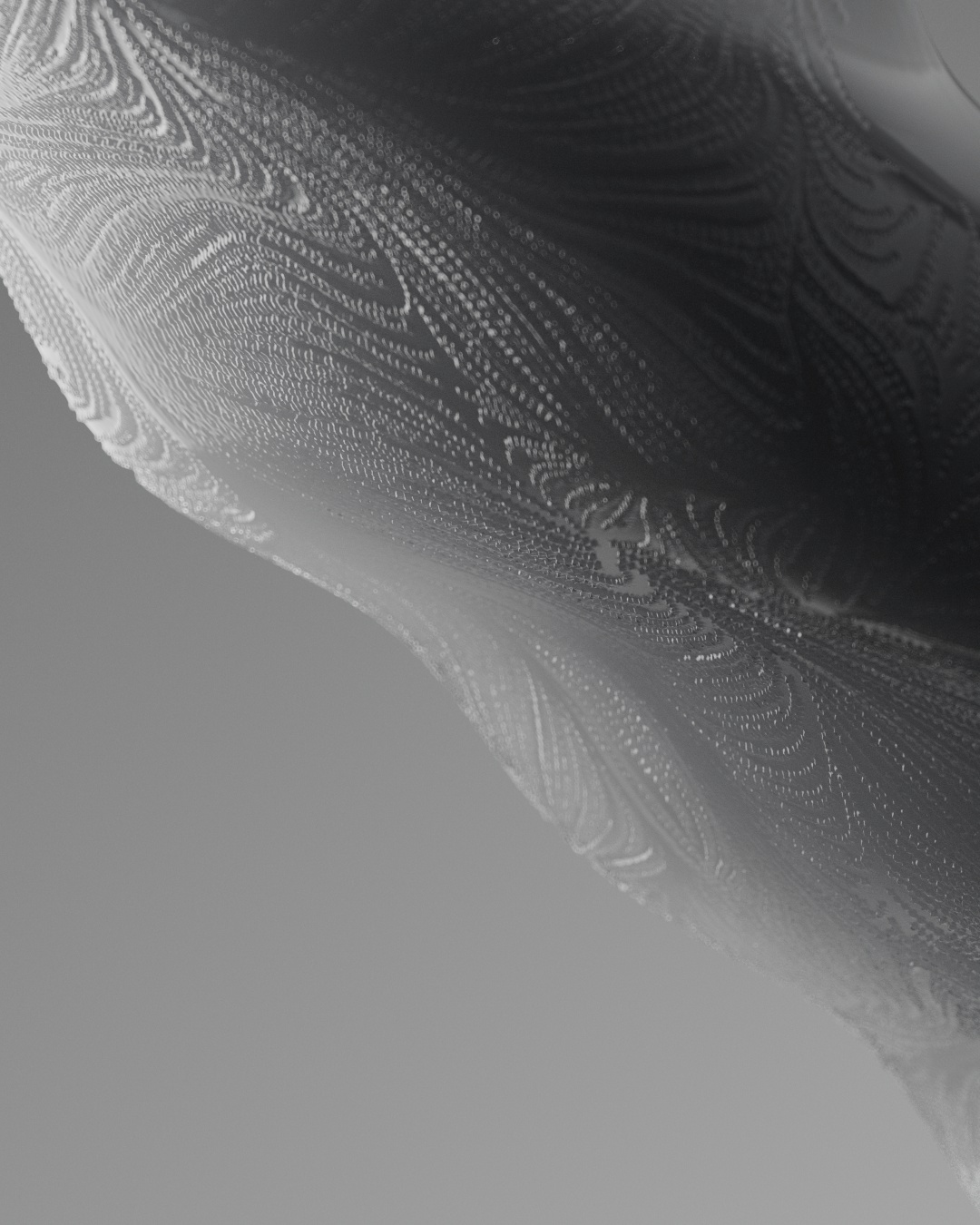

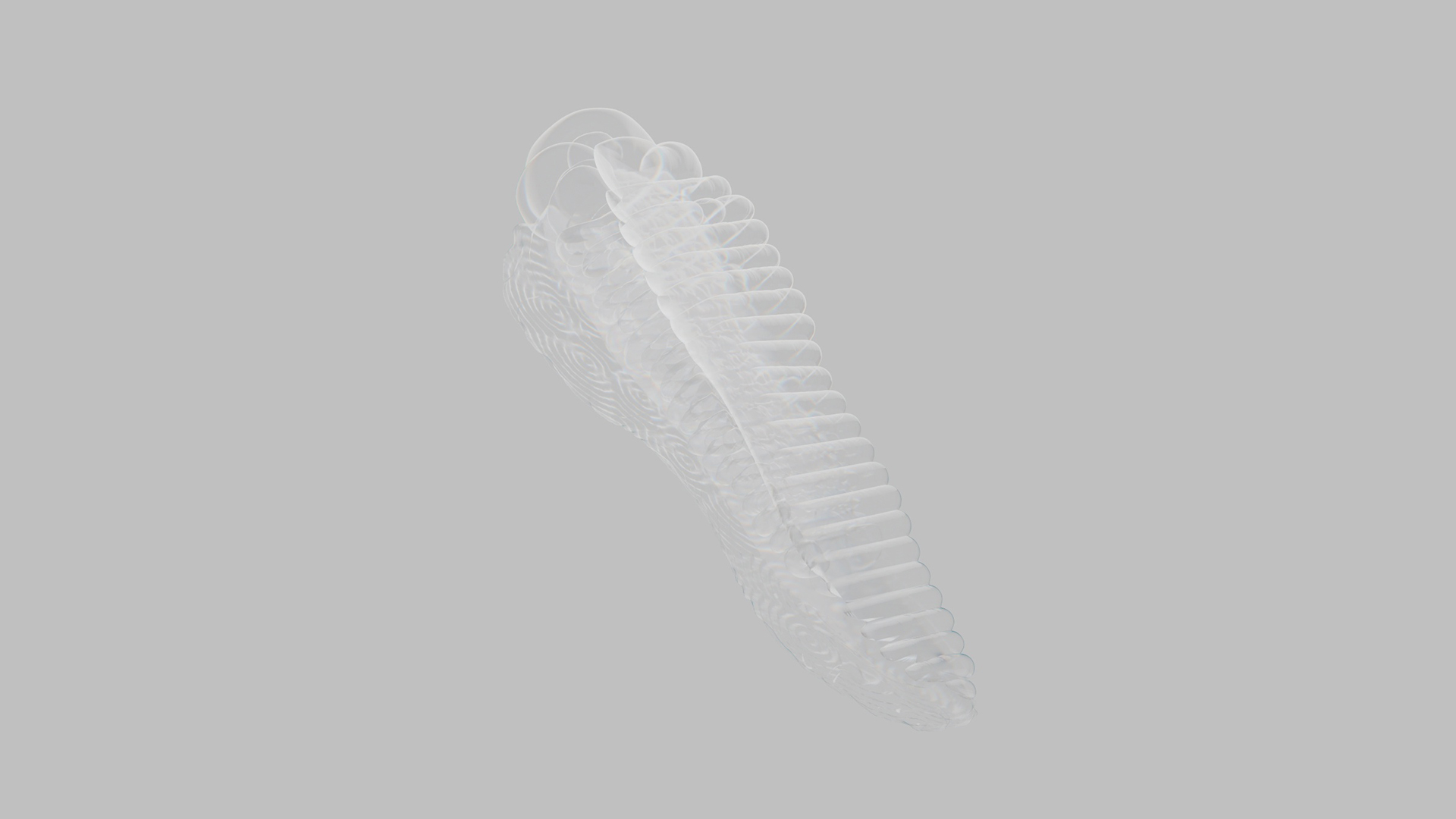

Our third item is the most future-oriented. It is a visual experiment about shoe soles that grow to adjust their shape for human feet. We created a series of abstract forms, which are examples of how this custom sole can morph to better support a foot and redistribute the pressure.

Credits

Creative Direction:

Maxim Zhestkov, Igor Sordokhonov

Design, Art Direction, Animation:

Sergey Shurupov, Artur Gadzhiev, Denis Semenov, Dmitriy Ponomarev, Oleg Zvyagintsev, Denis Semenov, Tatyana Balyberdina, Roman Kuzminykh, Kristina Avdeeva

Writing:

Anna Gulyaeva

Year:

2020

Contact us >

work@media.work

Follow us >

Instagram

LinkedIn

Spotify

Media.Work > USA

453 S Spring Street

Ste 400 PMB 102, 90013

Los Angeles

Media.Work > UK

71-75 Shelton Street

WC2H 9JQ

London

Media.Work © 2024